From ego to ECO

Architecture as a tool to rediscover the potential of the Land and the People.

Hi, I am Alex

The founder of Studio for Change & Build for Change

The reason why I pursued this path is the same reason why I decided to study architecture in the first place: it makes me happy!

My ultimate goal is to become closer to my true self. In doing so, I am not driven by the need to help others; the fact that it benefits others is a natural and beautiful extension of that process.

As Lilla Watson so powerfully said, “If you have come here to help me, you are wasting your time. But if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together.”

How everything started

My first job after completing my bachelor’s degree made me question the very purpose of architecture. I began to see it as elite, accessible only to a privileged few. Which seems counterintuitive if you think about it, it doesn't matter where you are or who you are, we are all constantly surrounded by the built environment. Yet so many times, we can witness how architects become more obsessed with the approval of their peers than with the experience of the actual users.

Thinking about who an architect is, I always remember how a professor during my bachelor’s studies remarked, “architects are the builders of the world”. I don’t remember who said it or in what context, but the phrase has stayed with me ever since. To me, it means that as architects, we carry the responsibility to actively shape the world others live in, with the foresight to create spaces that are both good and beautiful.

Yet somewhere along the way, architecture lost this sense of responsibility. It became preoccupied with projecting an image of beauty, driven more by wealth and power than by care for people. Beauty became superficial—a façade—without the depth of real meaning or connection to those who inhabit the spaces we design.

In this period of doubt, I encountered the work of Francis Kéré, shortly after he won the Pritzker Prize in 2022 (the architecture world’s equivalent of the Oscars). His approach, which I would describe as innovative simplicity deeply rooted in culture, transformed how I saw architecture. His projects touched me in a way no other architect’s work ever had. What struck me most, however, was not only the architecture itself but his humility, a rare quality in a field so often dominated by large egos.

His example set me on a new path, beginning with my master’s degree at Delft University of Technology. I enrolled largely because of one course that focused on architecture in extreme environments with little to no resources. This course took me to Sint Maarten, in the Dutch Caribbean, where we were tasked with designing affordable housing.

Visiting the island and speaking with residents made me realise, for the first time, the impact of globalisation and the export of Western construction models. Concrete and steel were imposed as universal solutions under the guise of progress, yet they resisted the local context and burdened communities instead of supporting them. The project brief itself also felt disconnected. It seemed to address those who already had housing, not the many families struggling paycheck to paycheck, especially in the aftermath of COVID, when the island’s economy had taken a serious hit.

At the time, I didn’t know exactly how to solve it, but I knew I wanted to design homes truly for those who needed them. In response, I developed an infill block made from paper waste and a modular structural system—an attempt to reduce imports, lower costs, strengthen the local economy, and address the island’s waste problem. This project became my passion. Yet as we moved closer to building a prototype, I realised I was rushing toward a product-driven solution without having fully understood the deeper causes of the very construction model I was questioning. I feared creating another universal solution, just in a different form, rather than addressing the real systemic issues.

Again, I was left with doubts and questions. But at least this time, I knew the direction I wanted to move toward. By coincidence, around the same time, I was invited to IIT Guwahati in India to study traditional architecture and explore new housing solutions. After an initial call with the team, only two months passed, and I was off to India. My personal goal was clear: to understand what drives the global appeal of the concrete-and-steel construction model.

I spent one month travelling through India and two more in Assam, in the northeast. At first, I struggled to find the answers I was seeking. But after many setbacks, I learnt to let go of my preconceptions, of the need to control the process and simply take things as they came. That shift changed everything. When I finally began listening without judgment, I could see more clearly the drivers, fears, and needs that shaped people’s choices.

Out of that experience, I laid the foundation for what I would later define as Contemporary Contextual Architecture (CCA).

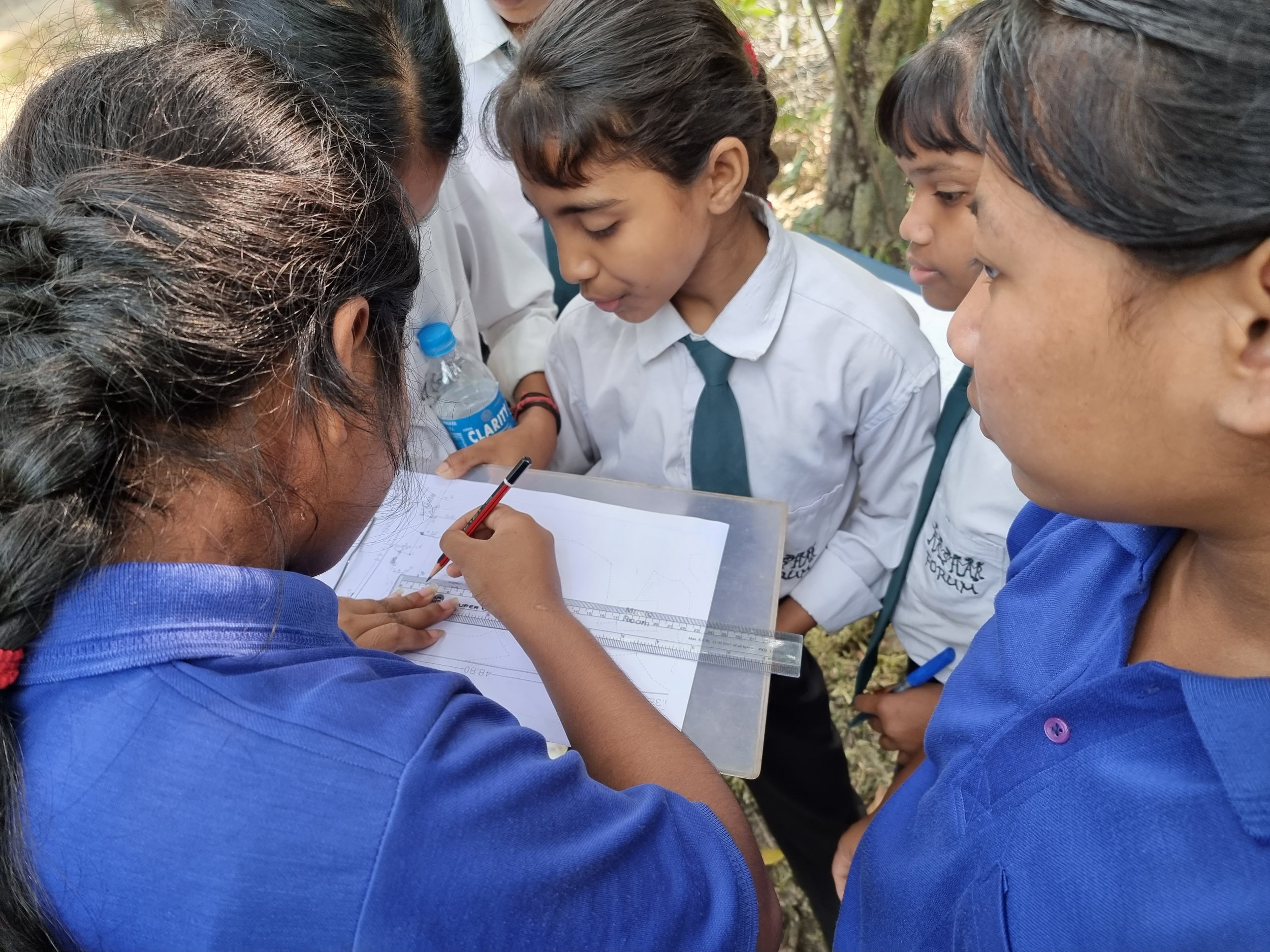

During this time, I was also fortunate to connect with the Akshar School in Pamohi. Working with them not only helped me refine the principles of CCA but also revealed the potential of architecture as an educational tool, one that can shape better environments, encourage dialogue, amplify voices, and inspire future generations to value building practices rooted in their heritage.

When I returned to the Netherlands, I continued this exploration. Over the course of a year, I researched and reflected on my experiences, transforming them into the framework that defines Contemporary Contextual Architecture today.

“Contemporary Contextual Architecture is a design method defined as a response to the current state of a specific context. It combines principles of traditional architecture with modern construction methods and a renewed understanding of local resources, including materials often treated as waste.

The final essential dimension is a genuine engagement with the user to move beyond function and aesthetics.

The innovation is not a return to traditional architecture, but learning from it to meet today’s societal needs, enabling progress that respects both people and planet while rooted in real human experience.”

After graduating in July 2024, I founded Studio for Change and Build for Change, two complementary initiatives united by a single vision: to promote Contemporary Contextual Architecture that connects people, place, and planet.

Together, the two entities form a mutually reinforcing model: Studio for Change donates 20% of its profits to Build for Change, ensuring that architectural success directly supports social and environmental impact.

-

Studio for Change operates as a for-profit architecture practice, taking a top-down approach. We focus on clients and markets with greater financial flexibility, allowing us to pursue high-quality, sustainable designs that demonstrate what responsible architecture can achieve. By setting a visible example of design excellence that benefits both people and the environment, we aim to inspire wider cultural and industry change.

-

Build for Change, on the other hand, is a nonprofit organisation that takes a bottom-up approach. It collaborates with local architects and communities in the Global South to co-design and construct schools and other public spaces that foster education, dignity, and sustainability.

Our goal is to prove that sustainable, human-centred architecture can thrive in every context, from the boardroom to the classroom, and that design excellence and social responsibility are not opposites, but partners in shaping a more equitable built environment.